On July 3rd, the 8th Circuit held that disparaging statements made by Jimmy John’s employees in a labor dispute were not entitled to National Labor Relations Act (“NLRA” or “The Act”) protections – because the actions were disloyal in nature and deliberately attacked the stores’ products. The full decision, titled MikLin Enters., Inc. v. NLRB, 2017 U.S. App. LEXIS 11792 (8th Cir. July 3, 2017) can be read here.

In 2007, employees of MikLin, a family-owned Jimmy John’s franchisee with ten sandwich shops in the Twin Cities area, sought representation by the Industrial Workers of the World Union (IWW). The IWW attacked MikLin’s sick leave policies, which did not provide for paid sick leave and required employees to find a replacement if they called in sick. The IWW spread thousands of posters around the Twin Cities area, stating that MikLin employees were not allowed to call in sick, and as a result customers were regularly consuming contaminated sandwiches.

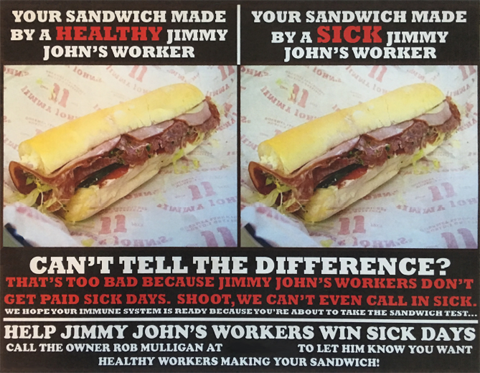

As shown below, the posters pictured two identical Jimmy John’s sandwiches, claiming that one was prepared by a healthy employee and the other prepared by a sick employee. The poster included quotes such as, “can’t tell the difference?” and “we hope your immune system is ready, because you’re about to take the sandwich test.” The posters even included the personal phone number of the vice president of MikLin, and encouraged readers to call him and complain about the sick leave policies in question. MikLin responded by firing the employees involved in the poster campaign and soliciting other employees to remove the posters from store areas.

An employer commits an unfair labor practice if it fires employees for engaging in concerted activities protected by Section 7 of the Act, including communications to third parties and to the public that are part of an ongoing labor dispute. The National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB” or “The Board”) held that the use of the posters was protected under Section 7, because protections are only surrendered if the communications are disloyal, reckless, or maliciously untrue. The Board further held that an employee’s public criticisms require “malicious motive” or reckless disregard for their truth or falsity. Finally, the NLRB concluded that because the posters related to an ongoing labor dispute and were not created with malicious intent, they were shielded with Section 7 protections and the employee terminations were improper.

On review, the 8th Circuit majority disagreed and refused to enforce the NLRB’s holding, in part because the NLRB’s interpretation of Section 7 exceptions (requiring “malicious motivation”) directly contradicted Supreme Court precedent on this issue, NLRB v. Local Union No. 1229, IBEW, 346 U.S. 464 (1953), better known as “Jefferson Standard.” The Court found that the Board also erred in concluding that the employees’ product disparagement was protected Section 7 activity simply because its purpose was to obtain paid sick days.

The opinion noted that the correct interpretation of Jefferson Standard was that employers are permitted to fire employees for making “a sharp, public, disparaging attack upon the quality of the company’s product and its business policies, in a manner reasonably calculated to harm the company’s reputation and reduce its income,” even when the communications in question relate to an ongoing labor dispute. Miklin, 2017 U.S. App. LEXIS 11792 at 14 (quoting Jefferson Standard).

The case addresses – but does not fully resolve – the role of truth or falsity in evaluating disparaging employee statements. The Court held that the Board erred when analyzing the issue of “truth or falsity.” While the Court did not state that falsity of communications was required to deprive employees of the NLRA’s protection, the majority did hold that a previous Board interpretation of the issue was correct: “employees may engage in communications with third parties in circumstances where the communication is related to an ongoing labor dispute and when the communication is not so disloyal, reckless, or maliciously untrue to lose the Act's protection.” Id. at 18 (emphasis added). Further, the Court cited to another disloyalty case holding that true statements are protected: “[p]ublic statements are protected when they are true and directly related to terms and conditions of employ.” St. Luke's Episcopal-Presbyterian Hosps. v. NLRB, 268 F.3d 575, 580 (8th Cir. 2001).

The majority held that the IWW’s statements regarding Jimmy John’s sick leave policies were in fact untrue, which presumably influenced its decision to overturn the Board’s ruling in favor of the employees. However, falsity may not be a necessary prerequisite to finding employee disloyalty. Jefferson Standard did not address whether the statements in question were true, choosing instead to focus on whether the statements were intended to harm the employer’s reputation and products. Further, the dissent cited a disloyalty case that explicitly stated: “[i]t matters not whether the communications were true or false.” Five Star Transportation, Inc., 349 N.L.R.B. 42, 46 (2007). While the issue is unclear, the Court did dedicate a portion of its analysis to the falsity of IWW’s claims on the poster. Therefore, employers and employees would do well to remember that the issue of falsity is one that can help (or hurt) any given case.

Regarding the statements on the poster, the Court reasoned that the information was false and misleading because employees were in fact allowed to call in sick; the IWW knew MikLin’s policy complied with Minnesota Department of Health regulations; and the attack was timed to coincide with flu season. The Court easily concluded that the attack was likely to outlive the labor dispute and unduly damage MikLin. The majority stated that the NLRA does not protect calculated and devastating attacks upon an employer’s reputation, products, and income. Because the posters were not entitled to Section 7 protections, MikLin management was free to terminate the employees, remove the posters from their stores, and solicit employees to do the same.

However, Board decisions were affirmed in two other respects: (1) a Section 8 NLRA violation was found where MikLin managers ridiculed pro-IWW employees on Facebook. The Court held that such actions act as a restraint on the exercise of Section 7 rights. (2) Removal of pro-IWW materials from stores also violated Section 8, again by restraining employees’ Section 7 rights.

Employers should always be wary about terminating employees who engage in pro-union activities. This opinion turned on the fact that the employees in question had purposely and directly targeted the company’s products and financial well-being, using false claims and unsavory scare tactics. The critical question is whether employee’s public communications reasonably target the employer’s labor practices or disparage the quality of the employer’s products or services. If no disparagement occurred, Section 7 protections likely still exist. Even in this case, moreover, two judges dissented from the majority opinion, so the legal protections for employee concerted activity remain a significant issue for employers to consider.

This case also offers another cautionary tale for employers regarding the use of social media and removing pro-union materials from the workplace. (See our prior postings on the NLRA and Social Media here). Employers should avoid actively restraining an employee’s right to organize or speak to third parties, lest they violate those employees’ Section 7 protections.

For more information labor relations, please review Chapter 3 of our Labor & Employment Handbook which can be downloaded for free here.